SDG target: Reduce the global maternal mortality ratio to less than 70 per 100,000 live births.

Most maternal deaths are preventable with tools we already have. The key is giving mothers high-quality care throughout their pregnancy and during childbirth.

Tragically, many mothers receive no care at all. One of the most searing images of inequality is a young woman giving birth alone.

Fortunately, many governments and their partners are innovating to erase this image. For instance, our partner Jhpiego is reimagining the way pregnant women interact with the health system.

Maternal deaths per 100,000 live births

Current projection

If we progress

If we regress

Most pregnant women spend a few minutes receiving care from a nurse or midwife several times during their pregnancy. One-on-one attention sounds good, but these meetings tend to be impersonal and rushed.

So in 20 health facilities in Kenya and Nigeria, Jhpiego invited groups of 15–20 women at similar stages of pregnancy to attend a series of two- hour group antenatal sessions. They got more time (as much as 30 times more!) with a health provider who got to know them personally. What’s more, they got to know each other— and build a support network that lasted beyond the pregnancy.

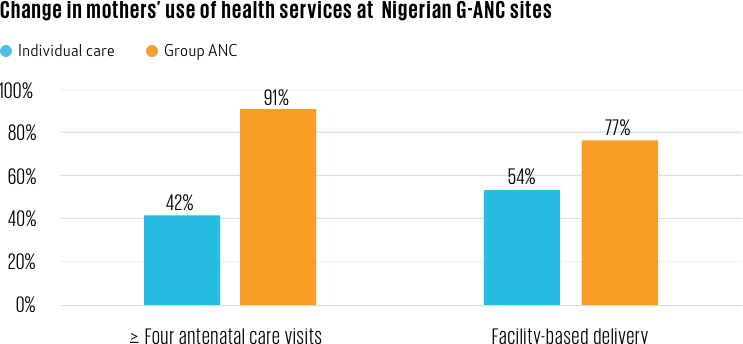

These group antenatal care (G-ANC) pilots achieved eye-popping results.

First, the care was simply better. In both Kenya and Nigeria, women in G-ANC were more likely to receive key interventions and information about how to care for themselves and their newborns.

Second, the women felt better about the experience, which suggests they are more likely to keep on using the health system. Nigerian women who participated in G-ANC were much more likely to give birth at a health facility, where the staff can manage an obstetric emergency.

Third, the women scored higher on an overall measure of empowerment, suggesting that G-ANC can affect not only maternal health but other important development priorities.

Although the project ended in 2017, all 20 test sites continued to offer G-ANC on their own, in part because the providers and mothers demanded it. The next step is to scale it up to other districts and countries so that the maternal mortality curve starts bending faster.

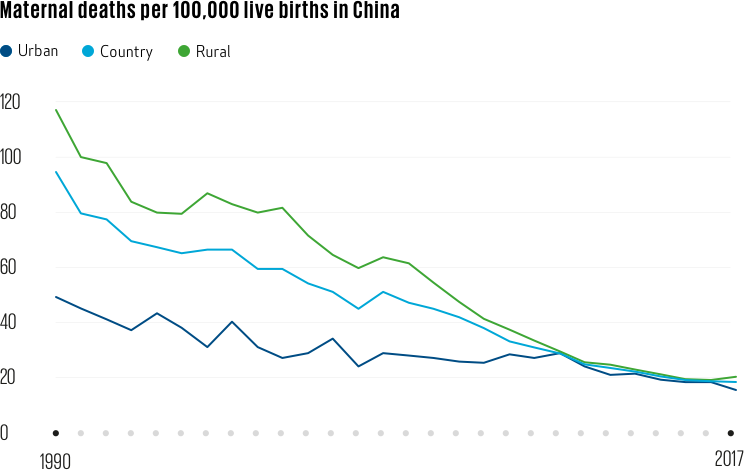

One country that has effectively scaled up maternal health is China. Thirty years ago, women in rural China were more than twice as likely than women in urban areas to die in childbirth. Now, that gap has been almost completely closed. Meanwhile, the national maternal mortality rate is less than 20 per 100,000 live births, well below the SDG target of 70. China achieved this equitable progress by investing in maternal and child health as part of the primary care system, improving the insurance system so that more people are covered for more services, and launching a maternal and child health campaign targeted specifically at poor families in Central and Western China.